This article by Maureen Carroll highlights some of work that we have been doing at REDlab. One of the main components of d.loft is a design thinking class at Stanford. The students go to the East Palo Alto Phoenix Academy to mentor the middle schoolers in an after-school design thinking class. This not only exposes the kids to design thinking and STEM, it is a valuable opportunity for the Stanford students to learn how to be a mentor and the importance of always having a prototyping mindset.

Learning from

What Doesn’t Work:

The Power of

Embracing a Prototyping Mindset

By Maureen Carroll, Ph.D.

Director, REDlab

Introduction

You can read all the books beforehand, but there is nothing

quite like the first moment you hold your newborn infant in your arms. Learning

on the job is really what parenthood is all about. That kind of immersion is

much like what Stanford University students experienced as they became mentors

to East Palo Alto Phoenix Academy middle schoolers during the Spring quarter.

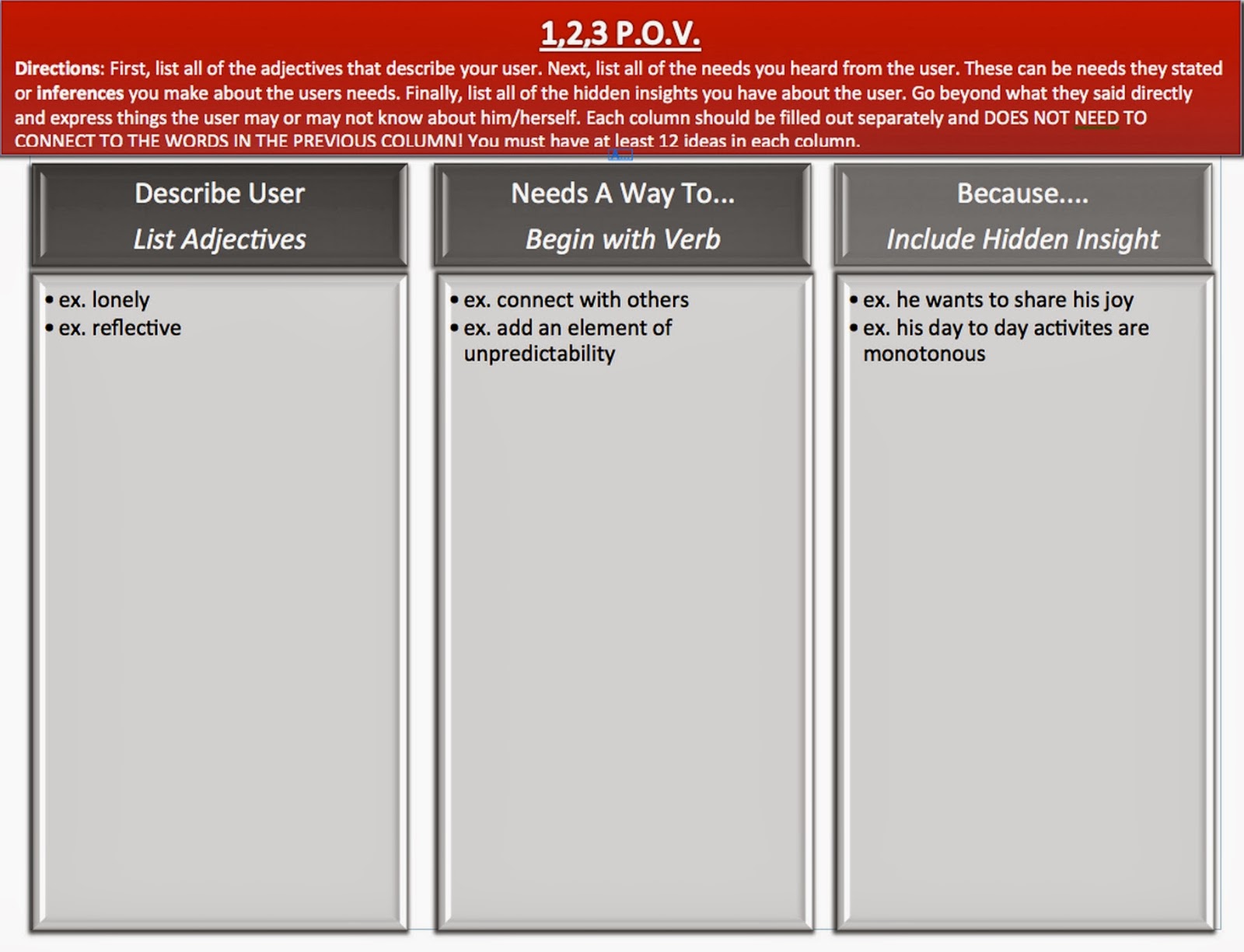

The students were enrolled in the class Educating Young STEM Thinkers,

which was part of an NSF grant called d.loft. The focus was to integrate design

thinking, mentorship and STEM learning. The students, who were a mix of

engineering, math, education, and science majors, were learning design

thinking- a human-centered innovation process- as they were teaching it. This

article highlights how this group of dedicated and passionate students dove

passionately into an experience that changed the way they thought about

learning in some very small and very big ways.

A

Prototyping Mindset

A prototyping mindset is characterized by the notion that

if you try something and it doesn’t work you simply learn from it and try

again. This mindset is an essential part of design thinking-it’s about failing

fast and failing forward. The Stanford mentors learned to be comfortable with

not knowing all the answers as they worked with the middle schoolers, something

that was not easy for them to do. What happened, though, was that they realized

that they were modeling the importance of making mistakes as a way to

learn.

One student described a activity where the middle schoolers

built tin-foil boats to learn about density and volume.

“I learned

that embracing that inevitability, instead of freaking out about it

or getting upset about it, usually makes everything work itself out...when

we were working with the students on the boat-building activity

and it turned out to be much easier than we expected, we all looked at each

other and said “oh well,” thought on our feet abut how to change it, and then tried the change out. The activity worked out

fantastically! The students knew that we had misjudged the challenge, but I think that seeing us react to our mistake in a

positive way helped them realize that we were human and helped us to make

huge steps as mentors.”

It wasn’t easy for the university students to show their

vulnerability, but when they did, they found that it helped create bonds with

the middle schoolers.

“I think

one thing I learned this week about mentoring is that as much as I feel

anxious about “messing up” in front of the students, it can

actually be a

good thing to show them that we are not perfect...our design challenge didn’t work out quite the way we wanted it to. The

students figured this out, but instead of it ruining the session, they laughed

with us as we tried to figure out how to

make it more difficult and then rolled with it. I think it helps to bring us to

an equal level of expertise, which is really important if we are trying to connect

emotionally with these kids.”

Teaching a prototyping mindset while learning what it was had a

strong impact on the university students. They were discovering their own

feelings about taking risks, making mistakes, and what role that plays in

learning as well as having to embody that mindset in their interactions with

the middle school students. One student described how being forced to lead

students even when she felt uncomfortable or unsure was a pivotal part of her

learning experience. A future educator thought about how he might incorporate

this into his own classroom one day.

“Reflecting on my own growth throughout the quarter, I am

becoming more cognizant of my discomfort with uncertainty. This discomfort

finds roots in a desire for something to be perfect. Two consequences

arise: I spend much of my time planning without getting feedback from my

“users” or my students, or I feel stifled because planning something

perfect is… impossible, actually. A prototyping mindset has directly

addressed this discomfort, and I want to internalize this mindset more and see

what it looks like in teaching.”

As the mentors and middle school students experienced what it

meant to adopt a prototyping mindset together they were able to push the

boundaries of learning. Becoming a 21st century thinker requires this sense of

resourcefulness. Through this experience, the Stanford students discovered that

they learned as much from the middle schoolers as they taught them. And that’s

always a good thing- in ways both big and small.